The Covid-19 pandemic, and the economic downturn that followed, added a new layer to the nation’s housing and public health crisis as more Americans found it harder to make rent payments on time.

A federal eviction moratorium and $46.5 billion in emergency rental assistance were meant to alleviate the problem, but by the end of August 2021, only about 11 percent of those funds had been distributed, and the moratorium had been nullified by the U.S. Supreme Court. (Though evictions continued during the moratorium because localities could interpret the policy with some latitude).

In Kansas City, Missouri, a group of tenants is working to address a mounting housing crisis on multiple fronts — by connecting tenants with legal support, disrupting eviction proceedings, and organizing tenant unions at buildings where residents experience housing safety issues.

KC Tenants’ work is conducted entirely by volunteers and guided by the belief that “the people closest to the problem are closest to the solution.” They rely on decades of housing data gathered and analyzed by partner organization Kansas City Eviction Project to inform their actions and efforts, and they continue to monitor state and county housing data, as well as data they gather themselves.

In the past two years, KC Tenants has successfully pushed for the passage of Kansas City’s Tenant Bill of Rights and established the Office of the Tenant Advocate. They are now mobilizing around a People’s Housing Trust Fund, which would dedicate public funding to “support the preservation and production of affordable housing.”

We spoke with four people associated with KC Tenants. Their perspectives offer more insight about housing challenges in Kansas City, and the work of KC Tenants to address a complex issue that impacts thousands of residents.

Perspectives below have been edited from interviews for brevity and clarity.

This story is equipped with a feature called SoundCite. Click on highlighted words with a “play” icon to hear directly from the subjects interviewed.

Sabrina Davis

Sabrina Davis has been a resident of Kansas City for 20 years. Now 62 years old, Davis was diagnosed with a severe autoimmune disease that ended her high-earning sales career when she was in her forties. Her income now consists of Social Security and disability payments. As Davis’s income diminished, it became more difficult to find stable and safe housing. She recently found temporary housing with a friend after “a nightmare” situation in her previous rental home. This summer, Davis became involved in KC Tenants’ North Star Team, which develops policy recommendations for city leaders.

With the help of her son and friends, Sabrina Davis prepares to move from her rental home in the Marlborough Heights neighborhood of Kansas City, MO, after exorbitant electricity bills led to a dispute with her landlord and an eviction filing against her. Davis has become an active participant in KC Tenants’ North Star Team, which takes policy recommendations to city leaders.

For the last 15 years in Kansas City, I’ve had a really difficult time finding any type of good place to call home. I’ve moved four times, and every time I thought I was going to a better situation, when in actuality, I was going into an even worse situation. The last property I rented was an absolute nightmare to live in. Before I moved in, the landlord told me the electric bills were under $100 per month, but the place had faulty wiring, and my first bill was $366. Each month, it only went up from there. My largest bill was more than $1,500, even though the home was very small, only 700 square feet.

I had an inspector come out, and he was so upset with what he found that he didn’t even charge me the inspection fee. He told me to get out of the house as soon as I could because the house could catch fire at any time and there was no fixing it.

Every month, I complained about the problem, and the landlord said it was on me to figure out what was wrong, and then he filed an eviction out of retaliation. It was through KC Tenants that I found legal representation, and I just got the judgement back a few weeks ago — in my favor. The judge ordered the landlord to pay me back all the rent I paid the entire time I lived there, the security deposit, and he has to pay all the attorneys’ fees. But I had to move out.

Now, technically, I am homeless. I’m not on the street, but my neighbor from years ago knew of my situation and she let me come stay in an extra room in her apartment. It was just for a month at first, but then she realized how hard it is to find something when you’ve had an eviction filed against you — no landlord is going to talk to you because you’re high-risk. But now that my case is settled, hopefully I’ll be able to find something soon.

I started following KC Tenants when they were just getting organized. I liked what they stood for and what they were trying to accomplish, and when I started having trouble with my landlord, I went on Facebook and told my story and several of the KC Tenants leaders spent hours with me and saw some of the things my landlord was doing.

They asked me to join the group, and now I’m a leader with KC Tenants, on the North Star Team. We go to the mayor and city council and talk to them about ordinances we’d like to see passed. We have the People’s Housing Trust Fund that we’ve been fighting to get passed, and this year, we were invited, as part of the Historical Tenant Delegation Team, to go to the White House and speak with President Biden’s advisor and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen. It was an incredible trip.

I just love being part of KC Tenants. They stand for their community. They want to see people thrive, and nothing short of that will work and is good enough, and they’re working hard. They work really, really hard researching and digging into solutions to help.

We want social (public) housing, and it’s possible. It’s happening in other places, and it can surely happen here, and Kansas City could be the first in the United States to do this. So, I’m in it for that. I am not leaving this group. They’ll have to drag me out screaming because I love the advocacy that they do. I love the outreach and everything, and I am just so into it.

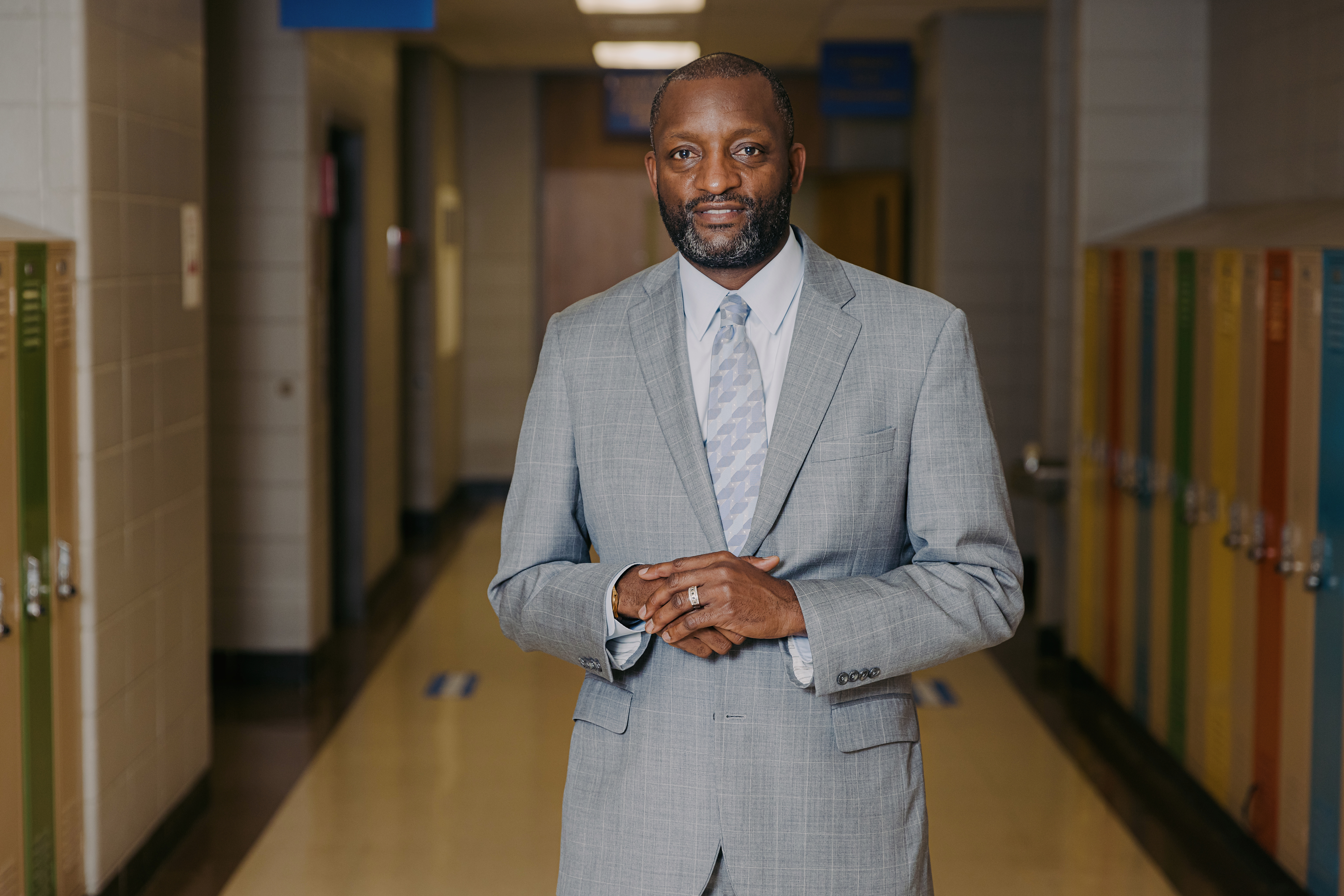

Mark Bedell

Mark Bedell is superintendent of Kansas City Public Schools, which has experienced student mobility rates (the number of students changing schools for reasons other than promotion) as high as 60 percent in some of its schools. To help students’ families, KC Public Schools launched its Justice in the Schools program in 2018 to connect families with legal and social support. The program won the Council of Great City Schools Award in 2019 for using data to innovate, and the district has been working with KC Tenants to better understand housing problems and advocate for change.

Our schools were already dealing with a lot of instability with housing before the pandemic hit. We were experiencing around 40 percent student mobility, and a couple zip codes we serve have the highest eviction rates in the state. The pandemic has only compounded the experiences we’re having — kids have just fallen off the map, just disappeared.

When we saw that eviction rates were high — in some of our schools, 60 percent mobility — we started an initiative called Justice in the Schools to help families who were being evicted, in some cases wrongfully evicted. We partnered with legal services and found funders to put money together for that initiative.

Students can bring their parents into Justice in the Schools. We’ll help them with more than just dealing with evictions. We help with housing issues, landlord-tenant law, family law, guardianships, domestic violence protection, foreclosure, health care. We help them with food stamps and Medicaid-related issues, car loan issues, denial of unemployment benefits. We help our families on so many different fronts.

But kids have got to have stable housing. I was a homeless kid growing up. I was a ward of the state. I lived in different homes. I know the impact unstable housing can have on a kid and the frustration they show up with and how it’s an impediment to kids being able to reach their full academic potential. So, we feel we have a responsibility to try to control for that variable to the best of our ability. But it makes this job so much harder.

If you think about a school where four out of 10 kids who are there at the beginning of the year aren’t there at the end of the year, and those four kids are replaced with four different kids, it’s always a reset. You can’t get into the flow of building that relationship and being able to know these kids from August all the way through the end of May. It’s very difficult in a lot of our neighborhood schools to accomplish that.

When we look at kids who’ve been in our school district for two years or more, most fall within the range of how kids perform across the state. But the kids who have a lot of mobility, they’re two years behind because of all of the stuff they’re having to deal with. That’s why we started Justice in Schools.

And then there’s KC Tenants, which has been wonderful in providing us with data and utilizing our school district, in essence, as the primary district that’s been affected at one of the highest rates. They’ve been able to push some policy reform here in the city, and we are pretty aligned [with KC Tenants] on what we believe needs to be done and how we need to advocate on behalf of the families we’re all fighting for.

We’ve got to figure out — how do we move this at the state level, and potentially at the federal level to really get sustainable things done? So, I’m going to continue to support their work and do what I can to support their efforts to try to make sure that we have more stable housing here in this city.

Magda Werkmeister

Magda Werkmeister coordinates the KC Tenants Hotline, which provides support and resources for callers across the area who are experiencing unsafe housing conditions and evictions. Werkmeister is a student at Swarthmore College near Philadelphia, where she studies education and English. When campus housing closed at the beginning of the pandemic, Werkmeister returned home to live with her parents in Kansas City, where she became involved with KC Tenants.

What really drew me to KC Tenants was the feeling that you don’t have to wait to graduate college or complete any formal training before you can make immediate change in communities, and I love the principle that the people closest to the problem are closest to the solution.

The KC Tenants Hotline is one of three major teams within KC Tenants. We take in calls from tenants or folks who have already been evicted and are already experiencing homelessness. We take calls from people in crisis or people who have questions, and we try to connect them with resources that might be able to address their situations. Of course we know, as an organization led by tenants, that there aren’t enough resources, right? If rental assistance solved everyone’s problems, KC Tenants wouldn’t have to exist.

And we know, with the CDC eviction moratorium ending, it’s only going to get worse. But even during the moratorium, there have been a lot of folks who have experienced eviction just because it’s complicated to actually be protected under the moratorium, which only covered evictions for nonpayment to begin with.

There are also people who call us who have evictions on their record, and now they’re trying to find a new place to live and they’re just being turned away at every single place. There are a lot of folks experiencing the inability to pay rent, because so many people have lost jobs during the pandemic, and Kansas City is one of the top ten places in the country where rent is rising.

We also have a lot of folks who are experiencing unhealthy conditions in their homes, different kinds of maintenance issues that are going unaddressed. In the summer, we heard from a lot of folks who didn’t have working A/C, and their landlord wouldn’t fix it, or their utility costs were way too high.

So, we partner with several legal organizations in the city who provide pro bono services to folks who are experiencing these things. We refer folks to the Heartland Center, for instance, for legal aid. We know those organizations are overloaded because there are so many people going through the same thing. But because we have an established connection with them, it’s a little faster for the tenants we refer to get connected.

And then rental assistance is hard to navigate because there are a million different programs with different sets of criteria and eligibility for each one. We do the work of trying to keep up to date with which ones have funding, which ones don’t, what the specific eligibility requirements are, and we share the ones folks will actually be eligible for.

There are so many people who really believe in housing as something that people deserve just for being people. Our organization is based on relationships. It’s based on being accountable to each other; it’s based on knowing where our strengths are and being honest about what we need to improve. I think a really good community is formed when people come together with the goal of making sure that people have access to decent housing — not only for ourselves. We believe everyone should have that.

Jordan Ayala

Jordan Ayala is an economics Ph.D. candidate at the University of Missouri – Kansas City, a research scholar with the OSUN Economic Democracy Initiative at Bard College, and a member of the KC Tenants Strategy Team. Raised in Kansas, Ayala spent much of his twenties traveling and working in music and music education. After returning to Kansas City to continue his education, he joined KC Tenants in early 2020 to organize, support actions as security and police liaison, and eventually began to conduct data research and fight for housing rights.

I’ve tried to engage in things that amplify my community. I’m Mexican-American, second-generation, with roots in a historic Mexican-American community of the Westside neighborhood in Kansas City, which is like one of a few sites of straight-up gentrification, with the so-called creative class taking over at least half the neighborhood. So those connections in my past are what always had me paying attention to this stuff.

I think there’s just no way to do the work I’m interested in around housing justice, around really securing these economic rights to housing, to employment, to health, to education… alone. You cannot do that in a technical space. This needs to be a space that is open to everyone to participate. My niche is data and participatory research.

Due to, I assume, the influence of the real estate lobby and the power of the real estate industry in general, all eviction records are public in the whole state of Missouri, so anybody’s eviction record — a filing or court-ordered eviction — is available. That is not the case in most places. But because it is the case, we have a very rare data set. If you talk to other eviction data researchers, having this level of data makes things a lot more straightforward.

Earlier this year, during Zero Eviction January, one of our data team members wrote a new script for accessing this information.Our data team worked together with the KC Eviction Project to create a comprehensive data set. Now we have all the counties in the metro area, plus all of Missouri going back 30 years.

And we now have more data than the county does. There’s a lot they discard as they make changes in the system, so we have the most robust information set possible for this area. That makes it so we can say, “You attempted to evict people over 900 times, there were this many attempts, this many acts of violence towards these people trying to push them out of their homes.”

Democratizing access to information, getting people to participate in this information-creation process, in this knowledge-creation process — that, for me, is life-giving. It’s a beautiful thing. Like, how can I use these tools and interact with people? How do I learn with other people? It’s through this collaborative effort that we’re all learning different stuff.

I still work 50 to 60 hours a week on my other work, and I’m doing this on top of it. We have people who have two kids who are spending 15 to 20 hours on top of working full-time — whatever they can. Yes, they’re getting something out of the community, for sure, but there’s no material reward in the sense of income.

But we are here to center the voices that are not a part of the conversation, the voices that have been discarded or actively oppressed. This is our place. And this is a city that has changed rapidly, is changing rapidly, and that’s why we’re here. We have a lot of knowledge and expertise to be in these spaces, to do this work, to devise these policies. We’re not children, right? We know what we’re doing.