About 75 miles west of Washington, D.C., and “75 years back in time,” as the saying goes, lies Rappahannock County, a popular weekend spot for city-dwellers who enjoy the area’s scenic vineyards, orchards, and farmland.

It’s one of the smallest counties in the state, with views of the Blue Ridge Mountains to the northwest, and home to a portion of Shenandoah National Park.

For decades, strict zoning and conservation codes have insulated Rappahannock from the residential and commercial development that’s come to neighboring counties, like Fauquier and Culpepper.

But this has not insulated the area from growing income inequality. In fact, Rappahannock ranks in the top 2 percent of US counties when it comes to income disparities, according to a 2017 community assessment.

“The rich are getting richer,” says Mimi Forbes, who manages the Rappahannock Food Pantry in Sperryville. “The poor are just staying where they are. They’re not really getting anywhere.”

There are no traffic lights in Rappahannock’s small settlements, no fast food restaurants, no strip malls, no industry, not a single subdivision, nor a grocery store. But a handful of high-end restaurants, antique shops, and art galleries cater to urban tourists.

Dubbed “Sonoma of the South” by Virginia Living magazine, Rappahannock has become an alluring retirement spot for wealthy professionals from D.C., Charlottesville, and surrounding suburbs. As a result, home prices in the area have increased substantially, which has driven some long-time residents away out of necessity.

“I know about five families right off the bat that couldn’t stay in the county,” Forbes says. “And so they left. They had to go somewhere else, to find a place to live, to find work. You know, to be able to survive.”

Approximately 10 percent of Rappahannock residents and 16 percent of children are living in poverty, and those in the area’s top 1 percent income bracket earn 33 times more than those in the lowest income bracket.

In the past year, more than 300 families — almost 900 individuals — relied on Rappahannock Food Pantry for basic sustenance, many of them older residents in the community.

Quentin, who declined to share his last name, is one such resident who comes to the pantry once a month to supplement his grocery shopping. He moved to the area several years ago to be near his son. His monthly income is just over $1,000, and all of it comes from Social Security.

On one visit to the pantry in late January, Quentin waited out front in his old pick-up — the pantry implemented a drive-thru model during the pandemic. Volunteers came out to Quentin’s truck, and gave him a list of everything on offer so he could choose what he wanted to take home.

“They have been so nice to me that I can’t even explain it to you,” Quention says. “It’s the first time I’ve ever taken anything like this. I still feel funny about it because I always worked for whatever I got, but this really helps. If I could work, I’d be out there doing it.’

One this trip, Quentin only needed milk, eggs, and bread, which volunteers delivered to his truck window. When his vehicle had trouble starting again, volunteers came out to help him jumpstart the engine.

While the pantry’s exterior looks rather plain, inside it exudes all the charm and elegance Rappahannock is known for. It feels like the rustic, high-end grocery tourists might love — with fresh vegetables in wooden crates, freezers filled with frozen meats, and a warm, palpable sense of welcome.

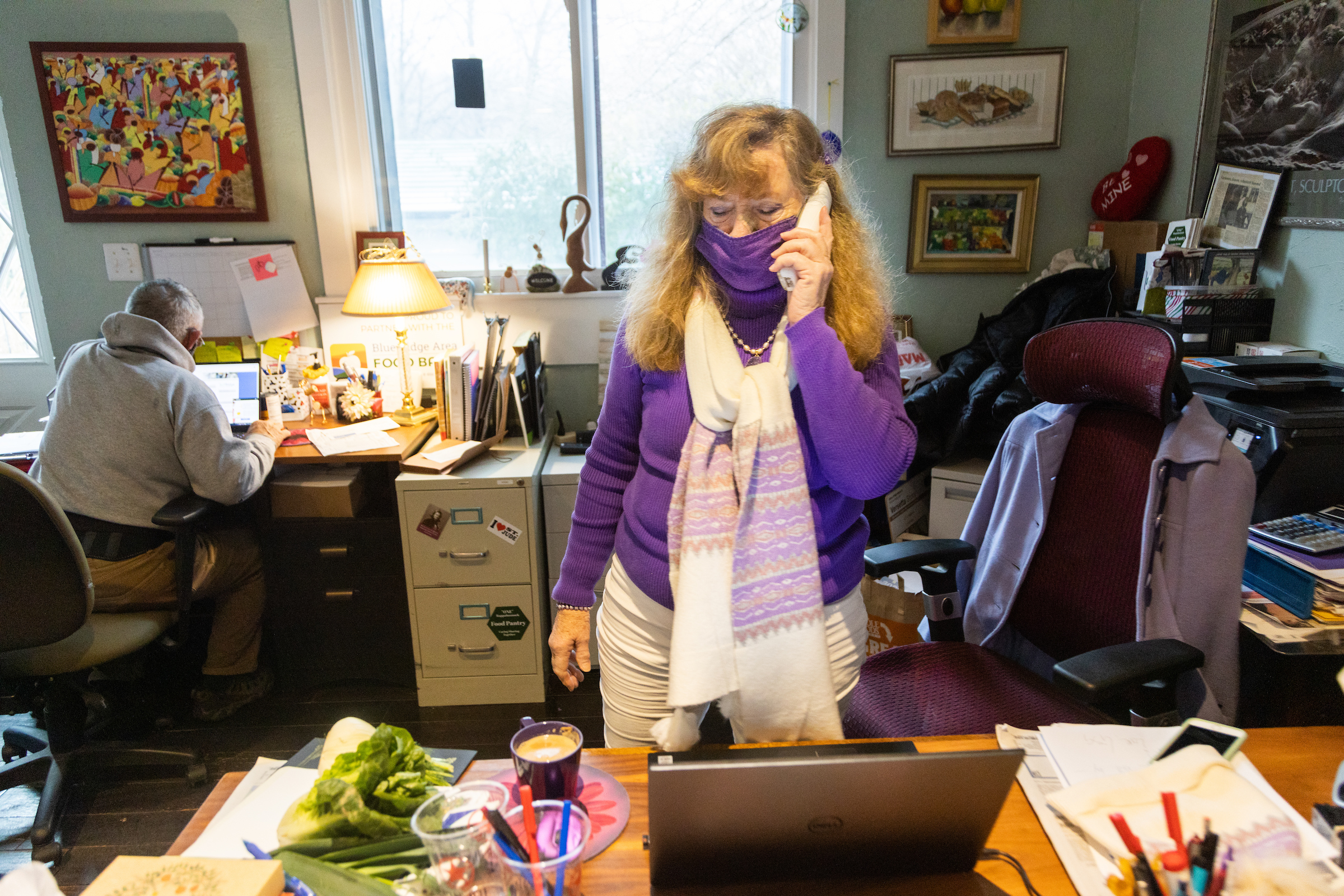

Rappahannock Food Pantry manager Mimi Forbes takes a call from her desk near the pantry’s entrance. She’s been managing the pantry since it opened in 2009.

Forbes’ desk sits near the front entrance, arrayed in purple accessories (her favorite color), so she can welcome volunteers, greet newcomers, and show people around.

The pantry has served more people during the pandemic, Forbes says, but it’s serving a smaller portion of the county than it used to as more lower-income residents move away to stay afloat. But Forbes also says her community is a humble bunch, and she wishes more people would make use of all quality ingredients on offer.

“A lot of people who live in my county should be coming to the food pantry and don’t because, ‘Well, I’m sure somebody needs it more than I do.’ But we’re going, ‘No! Nobody needs it more than you do. Why don’t you please just come to the pantry?’” she says.

Rapphannock Food Pantry sources its ingredients from the US Department of Agriculture, large grocery chains in the region, and another food bank in Winchester. In late January, with the area’s five-star restaurant closing for the month, the pantry received a donation of frozen salmon to share with clients.

Farmers and growers in the area also donate portions of their harvest to the pantry, which is partly how the nonprofit started — organizers asked farmers to plant an extra row and share it with the community.

Some people who use the pantry, like Dollie and Lewis Atkins, also donate when they can. Mr. Atkins, a proud gardener, loves to give away his excess crops, since he and his wife sometimes need support themselves. They’ve been coming to the pantry a couple times a month for a number of years.

“Older people have pride and they don’t want to burden nobody. They want to be very independent, so it’s kind of hard for them [to ask for help],” says Mr. Atkins. “But it’s like one big, happy family here.”

Beth Bailey is a relatively new member of the family — a volunteer who is also a recent transplant from Norfolk. She recently retired from a civil service job with the federal government, and moved to Rappahannock County with her husband, who is also retired.

Bailey began volunteering at the food pantry twice a month back in October of last year. She acknowledges she’s part of the trend that makes it harder for long-time residents to remain in the area.

“There’s the ‘been-heres’ and the ‘come-heres.’ I’m definitely one of the ‘come-heres,’” she says. “It is something the county really is spending time trying to tackle. I hope that I can be part of the solution — whatever that solution is.”

The county’s board of supervisors recently moved forward with plans for a mixed-used development called Black Kettle Commons, which will provide a new site for the food pantry, as well as — potentially — affordable housing units, a community center, and office spaces.

Forbes says she loves the building the pantry’s been using for the past several years. “However, we’re committed to serving all of Rappahannock, and this new location will be much better situated for people in poorer areas,” she adds.

The new space will be a permanent home for the pantry, offering more storage capacity within the building and more privacy to welcome new clients. The food pantry is planning to move to the new building in the summer of 2022.

“It will have everything we need,” Forbes says, “and the idea that there is affordable housing in the development is just phenomenal.”