Click the “play” button on the image above to watch a short film about Bikers Against Child Abuse.

This story addresses the topic of child abuse and may be uncomfortable for some readers and viewers. Please proceed with care. The Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline is available 24/7 across the United States and Canada.

The organization featured in this story uses “road names” to refer to its members and participating children, largely to provide more privacy around a sensitive subject that can involve legal proceedings. For this reason, subjects in this story are referred to using their road names only.

The bikers called her Dimples. “Because, if you got a good look at her, she’s got the cutest dimples you’ve ever seen,” says the man who would become her primary contact from Bikers Against Child Abuse (BACA).

He goes by the “road name” Coonie, a nickname tied to his Louisiana roots. At the time, Coonie was president of the Buffalo Creek Chapter of BACA — he now spends most of his time working in West Texas. When he met Dimples, she was living in a group foster home south of Dallas.

Coonie had come with several other BACA members to let Dimples know that they wanted to support her and make sure she never felt alone.

“She was just this little bitty tiny girl. She was sitting on the couch and wouldn’t speak, showed no emotion. You know, just… just there,” Coonie recalls.

Dimples was 12 at the time. She had already lived through a traumatic ordeal that began with abuse and ended in foster care. For a period of about five years, her stepfather had sexually and physically abused her, physically abused her older brother, and psychologically abused them both.

“We weren’t allowed to use the phone or the computer,” says Dimples, who is now 28. “We couldn’t go outside and play with a friend unless my stepdad decided he was going to let us that day. It was very controlled, and we cleaned constantly. If we didn’t clean something right, my stepdad would ransack the house just to make us do it all over again. We took care of everything, me and my brother. It felt more like we were slaves than kids.”

Dimples, now 28, became a “BACA child” when she was 12 and living in a group foster home south of Dallas. It was a CPS case worker who told Dimples about Bikers Against Child Abuse, an organization of bikers who are committed to empowering and creating safe environments for abused children. [Photo by Jim Tuttle]

Something a teacher said in a sex-education class helped Dimples realize that something was very wrong at home. “That was the first time I had ever heard anybody talk about it. Just like that, I was like, no, this is not okay. I don’t want this to happen anymore.”

What happened to Dimples happens to an estimated 700,000 children in the United States each year, according to the National Children’s Alliance, which runs Child Advocacy Centers across the country. While this is just 1 percent of children in the US, it’s widely believed that child abuse cases are underreported.

In 2018, child protective service (CPS) agencies across the country provided intervention for more than 3.5 million children. While there have been fewer reports of child abuse during the pandemic, researchers note that changing conditions are increasing risk for children, who now spend far more time at home.

Risk factors like job loss, high stress, and substance abuse are on the rise among parents, which could lead to new or worsening cases of abuse against children. At the same time, many reporting channels, like schools and churches, have been cut off, leaving neglected and abused children more isolated and alone with their abusers.

Such safe spaces and reporting channels were critical for Dimples. School is where she learned of her abuse, and where she told someone about it. But soon after speaking with a school counselor, another set of traumas unfolded.

Dimples was removed from her home by CPS, and she remained in the foster care system until she aged out at 18. Her mother renounced her parental rights and sided with her husband, who is still in prison today.

“I so wanted my mom to say, ‘I believe you. I love you. I’m not mad at you. But instead, that’s when the feelings of ‘this is my fault, I’ve just destroyed my family, I’m going to be alone’ — all those feelings set in, and my brother wouldn’t talk to me.”

After several foster placements, Dimples came to the group home. That’s when a CPS case worker told her about BACA, a group of bikers who wanted to help kids feel safe in the world. “I didn’t really know what they were going to do,” Dimples says. “But it was empowering to know they were coming for me.”

It was no wonder Dimples was shy and withdrawn when she first met Coonie and his biker friends. But Coonie quickly noticed the plush race car Dimples kept on her bed — a Jeff Gordon car. He was a big fan, too.

“Her adoption day came,” Coonie says, “and I wore a Jeff Gordon T-shirt because I knew that was my way of being able to talk to her. I knew she would talk to me as long as it was about Jeff Gordon.”

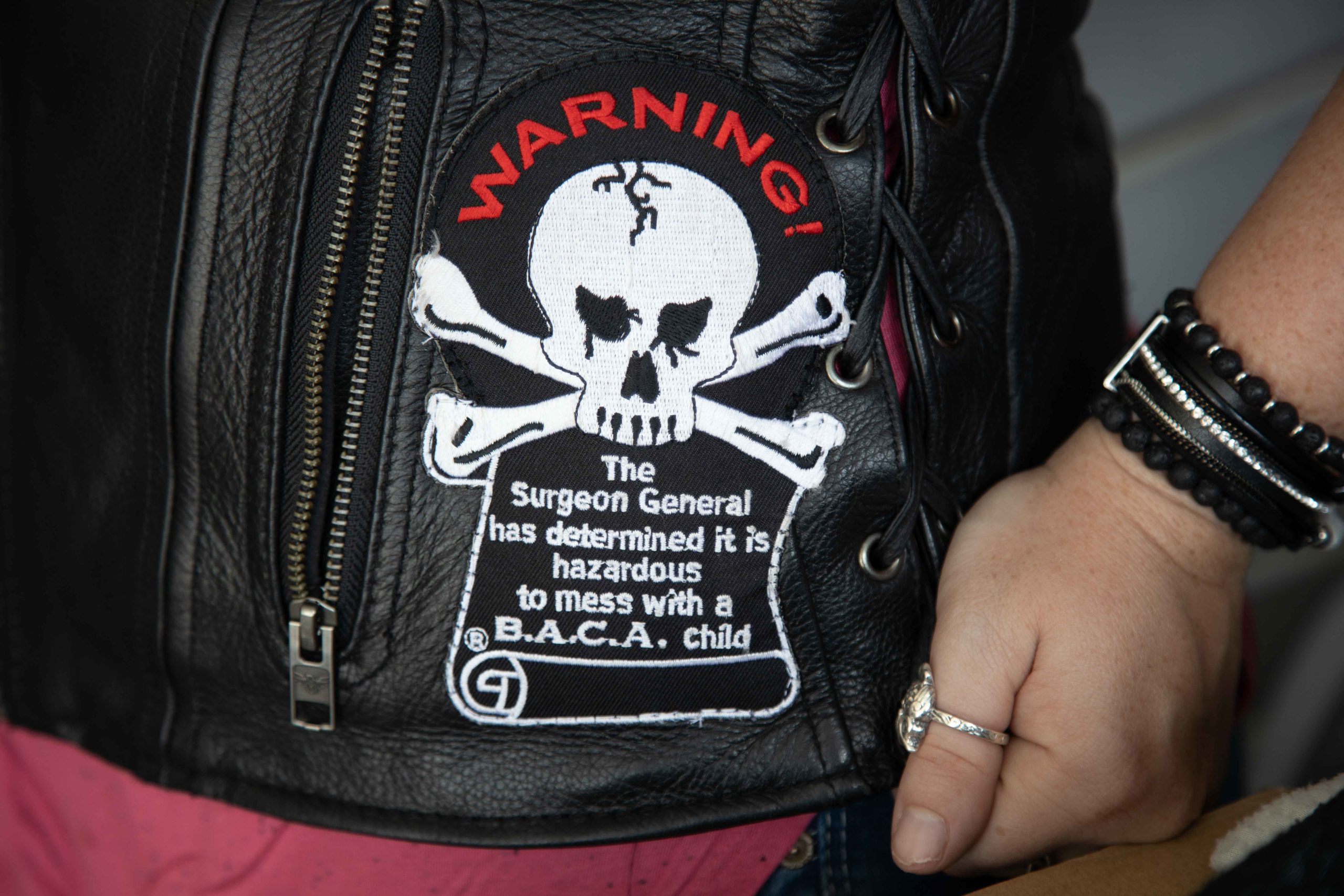

A BACA adoption is not a legal form of adoption, but a way to honor the child’s choice to welcome BACA as part of their family. The child receives a “road name,” which the child can choose, and also “a cut,” a vest adorned with BACA patches.

For Dimples, this meant she finally had a crew of people on her side. Any time she wanted or needed support, Coonie and his friends would be there.

“Gradually, she would start talking to me a little bit more and a little bit more,” Coonie says. “Never too much, you know, because of the trauma she went through — that plays a big part in how much a child will talk to you.”

Then one day, Dimples called Coonie at work. “I don’t know if it had just come to the point where she felt comfortable or what, but she opened up like a book and she started talking to me and telling me things.”

BACA members go through rigorous training before they ever meet a child, learning to provide support without becoming too unmeshed in a child’s life. BACA members never ask children to tell their story, and BACA is never provided that information, though child protective agencies refer children and families to BACA.

BACA members know they’re meant to play the role of supportive adult friend, not parent. They don’t take sides in a child’s legal case, but they sit in the courtroom, if it helps a child feel more comfortable and confident.

Once a child adopts BACA into their life, the child can stay as long as they like. They can even become BACA members themselves one day. “Once you’re a BACA child, you’re always a BACA child,” Coonie says, “even after you turn 18 years old — if you so choose.”

While many children decide to move on from their BACA experience — for any number of reasons — Dimples wanted to stay. “I know that as soon as I see that [BACA] patch, whether I know that member or not, I know they’re family, and I’m safe.”

As Dimples got older, BACA became part of her birthday celebrations. They were there for her graduation and her first tattoo. BACA members danced at her wedding, and it was Coonie who walked her down the aisle — a memory that still chokes him up.

“I realized Coonie had been my dad the whole time,” Dimples says. “He always had my back. Not once has he ever let me down. He’s always picked up his phone, even if it was as simple as a broken heart in junior high. When I got married, we really started having that father-daughter relationship, and every year it just grows stronger.”

Dimples is now a mom herself, to a three-year-old boy who calls Coonie “Pa Joe.” Coonie was there at the hospital, of course, when the baby was born, and Dimples asked two other BACA members, Lock and Key, to serve as godparents to her son.

Key (left), with Dimples and his wife Lock (right). Key serves as president of BACA’s Buffalo Creek Chapter, while Lock serves as a public relations officer for BACA’s Texas chapter. Over the years, Dimples got to know them both and their relationship grew stronger. When Dimples’s son was born, she asked Lock and Key to be his godparents. [Photo by Jim Tuttle]

BACA isn’t designed to provide such close family bonds for children who experience abuse; their mission is simply to empower children. But in this case, it just worked out that way. Because BACA was the first place Dimples truly felt at home.

“I was taught respect, what loyalty looks like, what family looks like,” Dimples says. “But they also taught me how others are supposed to treat me. I want my son to grow up strong and fearless. I know that as long as I’m with BACA, he will grow up with all of these amazing men in his life, and I know they will have a huge influence on him.”