The last day to register to vote in Texas is Oct. 5. The last day to request a ballot to vote by mail is Oct. 23. Early voting starts on Oct. 13 and ends Oct. 30. To find out about elections in your state, visit vote411.org.

Ofelia Alonso has never been scared of talking to people about difficult subjects. Growing up in a conservative family in the Rio Grande Valley in South Texas, the oldest of four siblings, she was known for being outspoken.

“I was always the rebellious one,” Ofelia says. “My parents nicknamed me ‘The Lawyer’ because I would always debate everything they said.”

The first to attend college in her extended family, Ofelia took an honors capstone class her freshman year where she researched abortion access in the Valley. Her professor connected her to a reproductive justice training held on campus, and it was the first time she heard people talking openly about the issue of abortion access. She attended more trainings, and soon she was hooked.

“I learned more and more about all these other issues that we have in the State of Texas. And it’s kind of hard to get out of it when you realize, everywhere around you, there’s just problems, there’s injustice.”

Now the 24-year-old is a field coordinator for Texas Rising, a Texas Freedom Network project aimed at organizing young people of color around social justice issues. She manages the organization’s activities across the entire Rio Grande Valley, from Brownsville to Mission, as well as the El Paso area, coordinating staff, volunteers, and chapter members. More than 90 percent of the population in this region is Latinx, a group typically overlooked by politicians from both parties.

“There was a recent poll that came out that showed the majority of Latinos have never been contacted by a campaign before,” Ofelia says “People don’t have information of who’s running, and it’s even more difficult for local elections.”

Ofelia Alonso hangs out in the kitchen of her father’s house with her younger brother, Fernando Alonso, Jr., and her two other siblings who also live at the house. Fernando works at Texas Rising as a deputy field organizer, where he started as a volunteer helping Ofelia. [Photo by Kelly West]

Texas has pitifully low voter turnout in general, and voter registration and turnout have historically been lowest among young people. But between 2014 and 2018, turnout among 18- to 29-year-olds tripled. Texas Rising and other organizations are trying to keep that momentum going, but in a state that ranks 46th in terms of voter access, it’s not easy.

“There are a lot of obstacles, but it all comes down to — the State of Texas makes it very difficult to register to vote. They refuse to have an online system. We’ve seen our entire lives shift online, but we can’t do something like register to vote, which is a form that takes literally 60 seconds to fill out.”

Although a recent order from a federal judge allows people updating a driver’s license to also update their voter registration online, most people registering to vote still have to print out a form and mail it in to their county registrar. To make registration easier, Texas Rising began mailing people voter forms with prepaid envelopes.

“We can’t even tell people, ‘Oh, just go to your nearest county building,’ because even though there should be a [registrar] and voter registration forms in every county building, we can’t guarantee that for a lot of people.”

Texas Rising sent out almost 300,000 voter registration forms to unregistered voters this year, and registered 21,100 people in person. Then in March, because of the pandemic, everyone was pulled from the field and operations shifted completely online, making it even more difficult to engage the community.

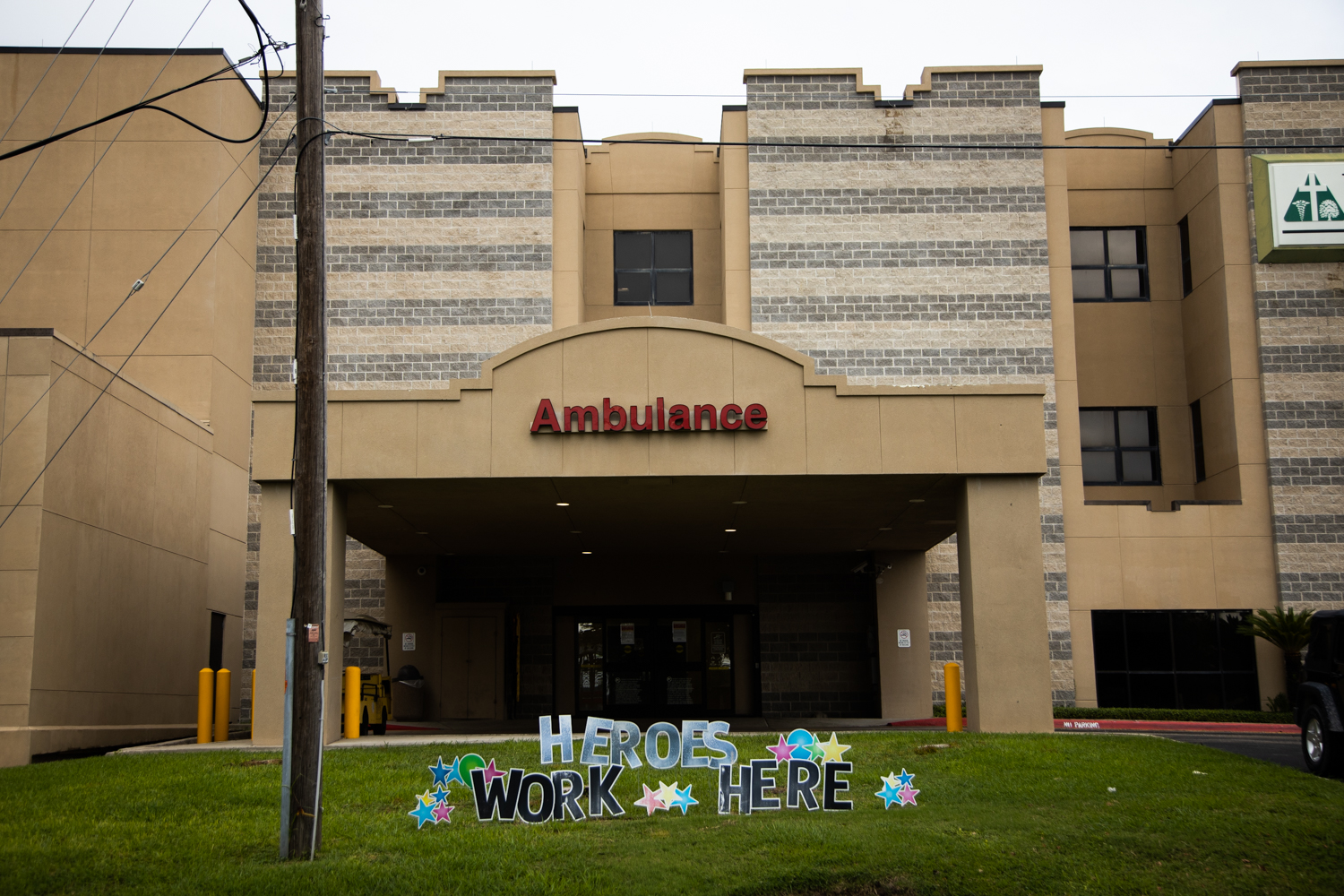

Ofelia used to live behind Valley Baptist Medical Center, where she says the sound of ambulances every night from COVID-19 patients arriving was too much for her, and she decided to move down the street. [Photo by Kelly West]

Over the summer, the Rio Grande Valley became a hot spot for COVID-19, overwhelming hospitals and funeral homes. Although the cases have declined, the area is still at the top of the list for confirmed cases in the state.

“All of a sudden it was like everyone I knew, someone in their family had died. Like Facebook was just obituaries for months,” Ofelia says.

Nationally, COVID-19 has disproportionately affected the Latinx population, and the Valley continues to feel the effects. Ofelia moved into a new apartment recently, partly because her old apartment was right next door to a hospital.

“Every single night, I would just hear ambulances all night, and it was getting to me. Seeing people go outside of the emergency room and pray, like 30, 40 people outside the emergency room every night. I couldn’t handle it.”

She worries about how the virus could affect her own family — her father works at a factory, and her mother runs a hair salon, so neither are able to work from home like she can. Her father, who had surgery earlier this year and is still recovering, is particularly at risk.

“It’s kind of like a waiting game – that’s how he sees it. It’s only a waiting game until he gets it because it’s not like he can just stop working.”

Ofelia goes to her dad’s house every week for dinner, where she and her three younger siblings get to hang out and reconnect. She worries about her father’s risk to COVID-19, because he works at a factory and can’t stay home. [Photo by Kelly West]

Before the pandemic, much of Ofelia’s time was spent canvassing on college campuses and visiting high schools to register newly eligible voters. Now she works exclusively from home, organizing phone and text banks, training people on new technology, recruiting volunteers, and trying to find creative ways to keep people engaged virtually. She also works with county governments to ensure they have the resources available to make voting accessible for the community.

“There’s so many projects going on all at once,” she says. “You have to keep track of all of them and make sure they’re all running smoothly.”

She’s also continuing to work on getting people to respond to the census, a difficult but important task in the Rio Grande Valley, which has been historically undercounted, analysts believe. There are many obstacles that make outreach difficult – fears related to immigration status, a lack of internet access in colonias and rural areas, plus, of course, a global pandemic that limits outreach efforts.

As of late September, Texas was 38th in the country for census response, with a self-response rate of 62 percent. Most counties in the valley had lower rates than the state average, with Cameron County, where Ofelia lives, at only 52 percent.

Ofelia recently moved into a new apartment, where she works from her kitchen counter most days. Texas Rising pulled everyone from the field and moved completely remote in March because of the pandemic. [Photo by Kelly West]

Sitting in the kitchen of her new apartment, her bedroom filled with boxes she hasn’t had time to unpack yet, Ofelia talks to some of her field managers on a video call. Her confidence as she walks them through their assignments belies her young age, and while she often hears skepticism about her generation’s commitment to political engagement, she thinks it’s a misconception.

“I think our generation is more aware than ever of all the things that are going on. And with that comes recognizing that sometimes things like voting, public comment — they come with a lot of obstacles and it takes a lot of privilege to be able to act on them. And yet young people are driving a lot of the movement that we see right now.”