In February 2016, I began documenting the community of people experiencing homelessness in downtown Austin. Over time, as a photojournalist, I have witnessed a collective narrative: People are experiencing homelessness together, not separately. There are those who stay hidden away. But mostly, I have seen individuals interacting with each other and forming a tight-knit community that hums along in and out of public view.

Then COVID-19 hit, dispersing members of this population. Even after artists painted bright murals of hope and inspiration on its boarded-up bars, Sixth Street still resembled a ghost town before a scaled-back reopening of businesses on May 22.

This storied thoroughfare is the hub of both the downtown entertainment district and the homeless community. It’s the corridor where people eat and sleep and congregate. It’s where romantic relationships form, sirens wail, and fights break out.

It’s where college students, sports fans, pedicab drivers, emergency personnel, street performers, and people just trying to survive without roofs over their heads all come together to create a wildly dynamic and often volatile mix.

Sixth Street is where I sit and kneel beside people on sidewalks, talking, hugging, inching closer and closer with my camera as I gain trust, one person at a time. It’s where I’ve met two of my dearest friends in this population, Catherine Fako and Shirley Erskin, physically frail women who are particularly vulnerable in the face of the coronavirus outbreak.

During the pandemic, I have maintained regular contact with Catherine, a bone-thin woman who goes by Cat and looks older than her 34 years. But I haven’t seen Shirley since March 23, when I dropped by her makeshift camp at Red River and Seventh Streets.

In recent months, Shirley Erskin was living at a makeshift campsite at the corner of Seventh and Red River streets in downtown Austin. [Photo by Camille Wheeler]

Several days later, I discovered that the camp Shirley had been sharing with her companion, Michael “Cowboy” Alexander, was gone. When I tracked Cowboy down, he told me that Shirley, who’d been working with a case manager to monitor ongoing medical issues, had been moved to a rehabilitation and skilled nursing unit in East Austin. The next morning, I called the facility, where an employee told me Shirley had been discharged.

Face mask on, I drove and walked through downtown, asking my sources on the street if they’d seen Cowboy and Shirley. The answer was no, and speculation varied widely as to where they might be.

Based on my recent conversations with city officials, I now have reason to think Cowboy and Shirley are probably living in one of the Austin hotels or motels established as interim medical sites for those considered high-risk for contraction or exposure to the coronavirus. These “protective lodges,” as they’re called, are run by the city’s Emergency Operations Center, which oversees a screening, assessment, and referral team composed of city employees from various departments.

According to Austin Public Health officials, more than 280 people have been placed in the four protective lodges, as well as a separate isolation facility for those with possible or confirmed exposure to the coronavirus. Members of the public who have tested positive for COVID-19 or who show symptoms, and are unable to safely isolate where they are, are encouraged to call the isolation facility intake line.

Ninety-five percent of the individuals placed in the protective lodges are people without shelter who have been living on the streets, said Chris Anderson, clinical case manager supervisor for the Downtown Austin Community Court, which provides comprehensive services to those experiencing homelessness.

The overall strategy involves the relocation of at-risk people from congregant living situations where self-isolation is not possible, and where spread of the coronavirus would move swiftly if a single individual in the community became infected.

I knew that Cat, through the assistance of her community court case managers, had been housed at one of the protective lodges, where residents receive food, clothes, medications, and connections to a wide range of professional care. The facilities are closed to the public and guarded around the clock by Austin Police Department officers.

I implored Cat to stay at the lodge as long as possible, but she wound up leaving after about two weeks. She said the bus ride to North Austin took her too far from downtown, and she had to walk from the bus stop to the motel, often in the dark, through an unknown neighborhood, where she didn’t feel safe.

Once inside her room, she suffered terrible loneliness. “Even though I’m very shy, I have to be where I can see something other than the TV,” Cat told me.

Catherine Fako and Daniel Fowler, known on the streets as Cat and Hobbit, are close friends and part of the glue that holds the downtown Austin homeless community together on Sixth Street. Hobbit prides himself on watching out for Cat, and she, in turn, often comes to the aid of her fellow citizens in need. [Photo by Camille Wheeler]

Even if Cat couldn’t bring herself to stay there, I thought I might find Shirley somewhere on the property. So one evening I parked my car just outside the chain-link fence surrounding the repurposed motel. I waited there in hopes of talking to someone who might know if Shirley was inside.

After several minutes, a resident named Sue arrived on foot for her nightly stay at the lodge. We chatted through my open passenger-side window, and I showed her a photo of Shirley. Sue said she hadn’t seen her anywhere at the facility, adding that locating people in the homeless community right now was “like trying to find a needle in a haystack. People are so scattered, it’s hard to find anybody.”

Continuing my search, I stopped by the community court on Sixth Street, where Cat and Shirley both have case management teams. I spoke with someone there, but court employees can’t divulge information about clients.

I expanded my search to other facilities considered supplemental shelters during the pandemic. At one location, an APD officer recognized Shirley by her photo. He sympathized with my efforts, telling me even professional social workers are getting bogged down in red tape as they try to keep tabs on people. Another dead end in my search for Shirley.

Cat, meanwhile, is back downtown, and things are tough. Her boyfriend is in jail again for beating her up. She recently learned that her ex, the father of her two children, died of a heroin overdose in Connecticut several weeks ago.

Cat stays up most of the night and naps during the day. She’s close friends with Daniel Fowler, a wiry man nicknamed Hobbit who prides himself on keeping Cat safe from violence. As for protection against COVID-19, Cat often wears a face covering, unlike some of her comrades on the street who believe that fears of the virus are overblown.

While Cat says she respects the coronavirus, she’s not afraid of it. She faced mortality at the age of 19 when she underwent brain surgery for the removal of two tumors. “I’ve grown to be tough,” she says.

On this spring afternoon in 2019, Shirley Erskin was still wearing her ID wristband after having just been released from a hospital. I worry about Shirley and want her to find permanent housing. She’s afraid of losing her community on the streets — of becoming trapped and isolated inside four walls. [Photo by Camille Wheeler]

What consumes her thoughts are picking up the clothes her mom mails to her at the community court, securing places to sleep where she won’t be robbed or attacked, and panhandling for money on Sixth Street and Congress Avenue, which, until recently, when bars and restaurants began reopening, was an exercise in futility on downtown Austin’s deserted streets.

Even though the world has changed during the pandemic, Cat says life feels much the same for her. “People treat me kind of the same as they did before,” she says. “I’ve always been social-distanced because I’m homeless.”

I first photographed Cat in December 2016, on Sixth Street, where she was clutching a sign that read “Kindness Matters Always” and protecting her dog from the cold.

Cat acknowledges that she’s been hardened by life on the streets. Certainly, she says, she is more bitter. But the photos I’ve captured of her — and of Shirley — reveal the softness and hope that still shines in their eyes.

I have seen Catherine Fako with her boyfriend, Turtle, numerous times throughout the years. In May 2018, I captured this photo of them together, with Cat’s dog. [Photo by Camille Wheeler]

About a year ago, I started giving the two women prints of the pictures I’ve taken of them. They have requested more prints, from various periods of time, and Cat decorated her temporary motel room with some of her photos. Shirley has even requested a photo album, and I allow myself to imagine the joy of someday delivering this gift in person.

I worry about both women, neither of whom have cell phones. When I’m downtown, I scan each block for the familiar figure of Shirley, a diminutive woman with white hair who often wears hospital scrubs and oversized men’s loafers as she pushes a shopping cart filled with her belongings, leaning on the handle for support as she ambles along Sixth Street.

Shirley is 67 and in poor health. She has high blood pressure and a long scar on her chest from open-heart surgery. When I last spoke with her, I wore my face mask but saw no sight of the one I’d given her to guard against the coronavirus.

I met Shirley in June 2017, and we’re comfortable enough with each other to argue. She wags her finger at me, telling me to be careful. Sometimes, almost in a conspiratorial whisper, she motions me close, telling me what she needs: clothes, money, a friendship ring that I purchased but haven’t delivered. I wish I hadn’t waited.

I want Shirley to find permanent housing. She’s been on Austin’s streets for two decades now. But she’s afraid of being trapped inside four walls. What if she moved into an apartment and no one came to see her?

Shirley, who is affectionately known as “Mama” on the streets, shares her life with her companion and protector, Michael “Cowboy” Alexander, who is rarely seen without his straw cowboy hat. [Photo by Camille Wheeler]

Shirley follows two rules for staying safe on the streets: know your surroundings and respect people’s property. She’s aware of the risks of living outdoors in downtown Austin, but takes comfort in knowing she’s part of a community.

“It’s not just me out here,” says Shirley, who soaks up the downtown nightlife. “It’s us.” Sixth Street, she adds, “has clubs, from this side on to the other side. So I go to either side. You get to meet new people, communicate.”

Cat feels the same way. “Even if I’m by myself,” she says, “and there’s a crowd of people coming out of a bar, hanging out, I’m not alone, even though I am alone.” And, as she and Shirley will both attest, bar patrons are often very generous with their money.

Through time, Shirley has revealed bits and pieces of her broken past. She lost her right eye in a car accident many years ago, and her adult son, Bobby Ray, suffered a stroke at birth and lives in a group home in Odessa.

Shirley is divorced, and her parents are long gone. She relies on Cowboy, who moved with her to Austin from the West Texas town of Brownwood in 2000. “I’m gonna keep him as long as God will let me keep him,” Shirley told me when we last spoke in late March.

As I continue searching for Shirley on the streets of downtown, I take comfort in knowing that Shirley and Cowboy are almost certainly weathering the COVID-19 storm together. When the pandemic is over, and it’s safe to resume normal social contact, I plan to give Shirley and Cowboy big hugs as soon as I lay eyes on them.

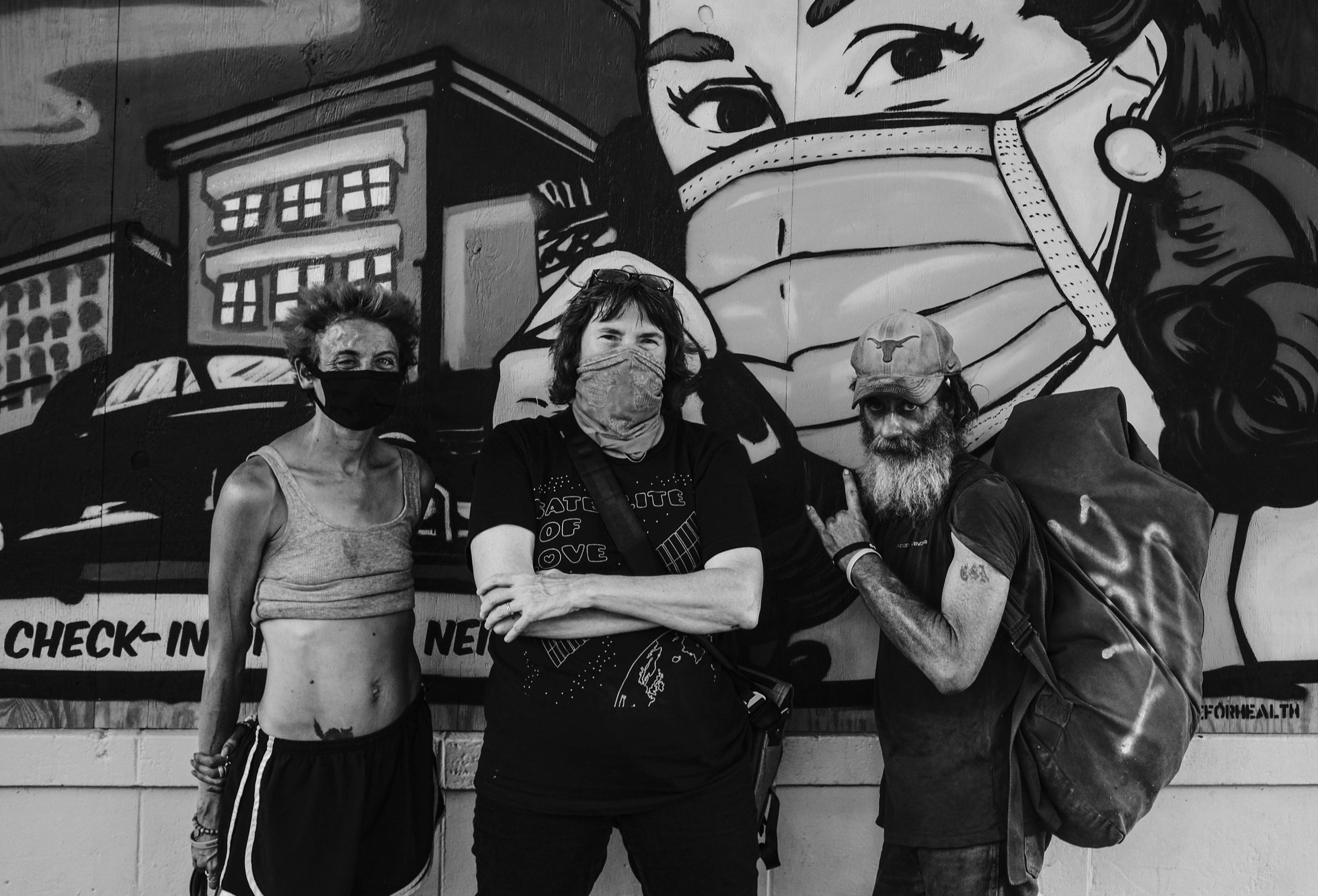

Photojournalist Camille Wheeler, center, with her friends Catherine Fako and Daniel Fowler on Sixth Street. Cat and Hobbit, as they are known on the streets, belong to the homeless community in downtown Austin. Camille has established a number of close relationships within this community since embarking on a documentary project in February 2016. [Photo by Daunte Clarke]

UPDATE

After the publication of this story, one of Shirley’s social workers reached out to photojournalist Camille Wheeler, with Shirley’s permission, and let her know Shirley was staying in one of the city-run motels established as an interim medical site for those considered at high risk of COVID-19. Camille and Shirley met that same evening outside the lodge. It was the first time they’d seen each other since March 23.