Before the COVID-19 pandemic locked down cities and forced many Americans to stay home, Patricia Evans liked to go to the Safeway or Dollar Tree in her neighborhood in North Oakland. “I always like to do things on my own,” Evans says. “But sometimes you can’t fool yourself when you need the help.”

That’s especially true now. At 93 years old, Evans belongs to a particularly vulnerable age group as coronavirus cases continue to increase in the Bay Area and across the country.

Thanks to a program called Oakland at Risk, Evans no longer has to worry about getting her own groceries. On a Monday afternoon in late March, her neighbor, Melissa Lee, drops off a bag of groceries at Evans’s apartment.

A trained psychotherapist before becoming a full-time mom, Lee typically spends much of her time volunteering with a local hospital to provide pet therapy and in-home hospice visits. But all of that stopped with the pandemic. Now Lee is here, helping Evans finish some of the chores she can’t do herself — plus a little extra. Lee also sticks around for laundry, bills, and conversation.

“That’s really what this is about,” says Lee, “making sure people aren’t alone.”

Patricia Evans (left) and her match Melissa Lee chat in Evans’ apartment on a day when Lee brought over some groceries. “When you’re accustomed to working and doing for yourself, you hate to ask,” says Evans, who had been looking for someone to assist her with daily tasks even prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. “I never was a person who liked to beg and ask. I always like to do things on my own. But sometimes you can’t fool yourself when you need the help.” [Photo by Martin do Nascimento]

Oakland at Risk is an effort started by longtime community activists Krista Luchessi and Paige Wheeler Fleury in Alameda County, California, to connect volunteers willing to lend a helping hand to those in need in their communities. The program matches healthy, low-risk volunteers with people in their communities who are older or immunocompromised and can’t easily run errands or grocery shop on their own.

“I’m hoping that, through this effort, we’re going to create much more close-knit communities and awareness of the value of every [member] of our community,” says Fleury.

Oakland at Risk started in mid-March, just as the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic and cities in California began initiating the first wave of lockdowns.

Luchessi, who directs a food-distribution organization called Mercy Brown Bag Program, realized quickly that the coronavirus would cause problems beyond the disease itself, especially for the vulnerable populations her organization serves. She and Fleury both feared the city’s seniors would become overlooked, left to fend for themselves — protected from the virus by stay-at-home orders, yet further marginalized from society.

“Nobody was thinking about how we protect [the older population], other than telling them to stay home,” Fleury says. “They need things.”

That same month, Luchessi and Fleury heard about a program in Kentucky called Louisville COVID-19 Match, which aims to connect Louisville’s high-risk residents with volunteers.

Inspired by a model thousands of miles away, they created a website for Oakland at Risk and immediately set out to spread the word. They posted announcements on the Nextdoor app and other social media platforms, and created a digital flier that people could print and share. Fleury also tweeted a reporter at the San Francisco Chronicle, who wrote about the program in his next column.

“We launched on a Sunday late morning and had 150 volunteers by Monday morning,” Fleury says. By the end of that week, they had more than 800 volunteers signed up. The program began making matches by zip code across the county as high-risk people reached out for help.

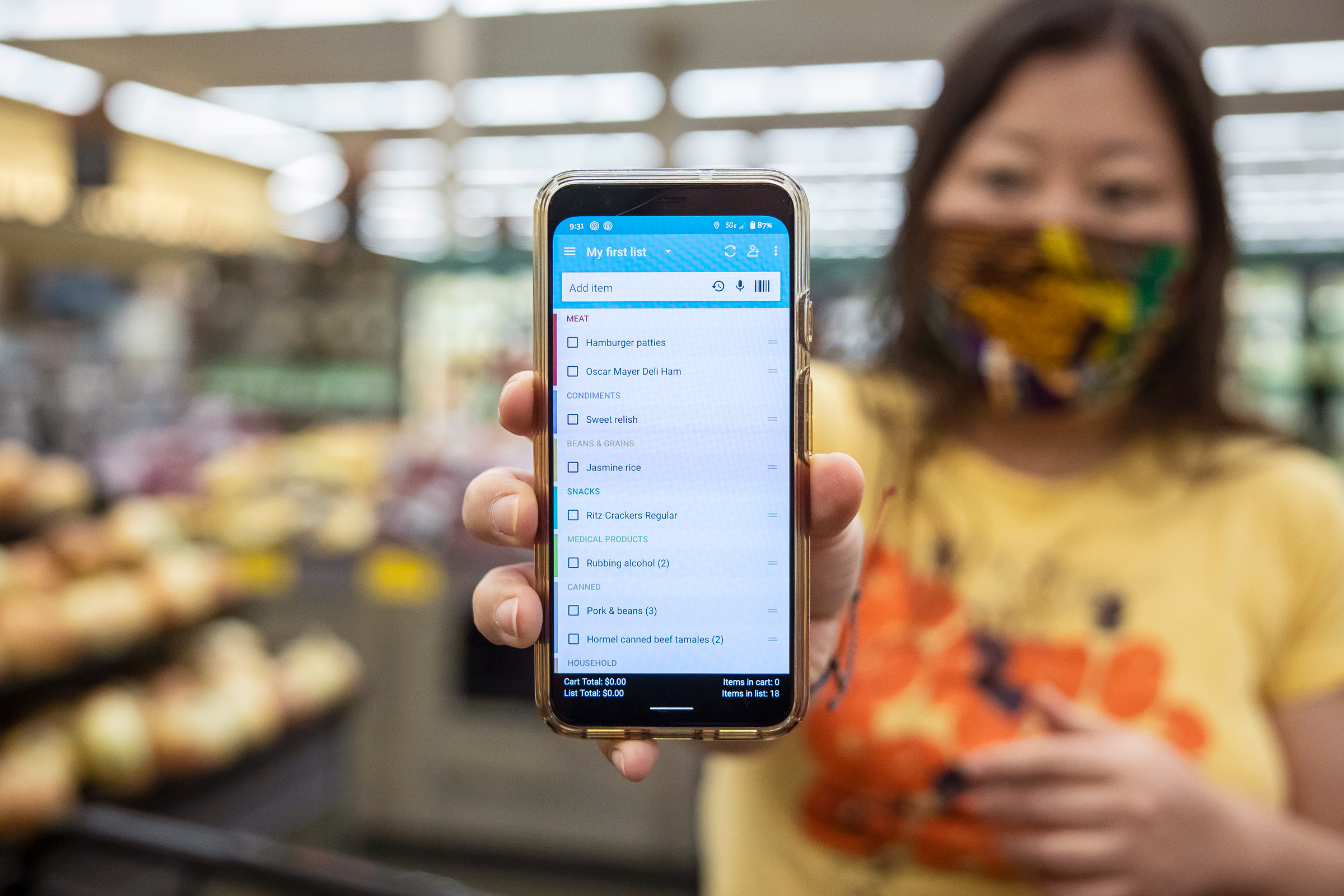

Julie Kang shops for herself, her husband and for Beverly Hoover using the Out of Milk app to coordinate between them. “Maybe I spend five extra minutes at the store,” says Kang of the time it takes for her to shop for her match, who reimburses Kang after every shopping trip. “Even if I had to [pay for] the groceries, I would still do it because it’s just my job as somebody who is able bodied. We have a car and it’s not like I’m afraid to go to the supermarket. I would like to believe that if the situation were reversed they would do that for me.” [Photos by Martin do Nascimento]

In East Oakland, Beverly Hoover and her husband, both in their 60s, felt a weekly grocery run would be too risky. “We’ve been avoiding grocery stores like the plague,” says Hoover, who saw Fleury’s announcement on Nextdoor and signed up. Within a day, Fleury matched them with Julie Kang.

“I’m not a medical professional, I’m not a first responder. I am a helper. I’ve always been a big believer in communities helping out each other,” Kang says.

Hoover and Kang started coordinating grocery lists over the app Out of Milk, where you can share lists in real time, so that Kang could start delivering what Hoover needed each week. For Kang, who’s no stranger to volunteering, Oakland at Risk has given her an opportunity to enjoy being of service to others. “I have some free time. I have a car. I love shopping for groceries,” she says. “It’s just something that I would happily do for anybody.” And something she’s done before, when volunteering as a driver for Meals on Wheels.

Oakland at Risk has also attracted first-time volunteers like Maxwell Stern, a 16-year-old student at Oakland Technical High School, who recently got his driver’s license and wanted to put it to use. Fleury matched him with Desiree Ann, a 33-year-old with hypertension and rheumatoid arthritis who lives near Stern in Oakland’s Montclair neighborhood.

“We’re so busy with our lives that we don’t really know the people who live next to us,” says Stern, who recently started grocery shopping for Ann. “I think that every kind of connection I make, or assistance I can provide, is just a really great way to build more community.”

And community is the goal — beyond connecting resources with those who need them.

For many participants, Oakland at Risk has helped them see new facets of their community. “This whole thing just makes me love Oakland even more,” says Kang. “People here know how to give help in ways that really count.”

For others, community is built through the individual relationships between neighbors, and the pandemic has fostered new bonds between neighbors who’d never met before. “In one case, [I matched a volunteer] with someone who’s 300 feet from the other person but never met them,” Fleury says. “I had a senior yesterday match with somebody in the same building, and they’ve both lived there for years and never met.”

For instance, William Heidenfeldt had never met his neighbor Jeff Crowl until Oakland at Risk matched them together, even though Heidenfeldt often walks his dog past Crowl’s home. In fact, they still haven’t met — at least not in person.

Each week, before Heidenfeldt drops off groceries at Crowl’s door, he gives him a call to check in. These check-ins sometimes turn into conversations — about the neighborhood, their careers, their families. “We’ve spoken at length over the phone,” says Crowl, who lives alone at 74 years old.

“I talk to [Crowl] more than some friends I’ve known for years,” says Heidenfeldt. “I hope someday to meet him.”

Volunteer Heather Davison has struck up a similar friendship with her match, Diane Scott, who lives alone in the Pill Hill neighborhood. A few times a week, they chat for 30 to 45 minutes about family, pets, politics, and so on. “People in my position are pretty much isolated and need that phone contact as well,” Scott says. “And I told [Davison] that if I get sick, she’s the person I’ll call.”

“[Scott] just needs someone to chat with sometimes,” Davison says. “And frankly, I like it too. I can see the relationship continuing after this pandemic is over.”

Heather Davison (left) and Diane Scott check-in with each other over the phone. “This community of older people is de facto invisible. They’re in their homes, many don’t come out and many live in these tiny spaces and we don’t see them,” says Davison. “They’re invisible and they’re wonderful, vibrant people with so much experience and we have so much to learn from them.” [Photos by Martin do Nascimento]

Back at her apartment, Evans finds a slice of homemade banana bread in her grocery bag, baked fresh that morning in Lee’s kitchen. “I’d like some of that right now,” she jokes, before deciding to save it for the next morning. “I love something sweet with my coffee.”

Lee occasionally adds little bonuses like this to Evans’ groceries. “I never knew my grandparents. They passed away when I was young, and both my parents passed away too,” Lee says, “so it’s just really nice to be able to do this for someone.”

Beyond her own relationship with Evans, Lee believes Oakland at Risk speaks to a broader phenomenon coming out of the pandemic, as people across the country began looking out for one another and bridging the gaps that often exists between neighbors. “I think [this situation] is going to really deepen that awareness of how important human connection is.”