With regular caseloads of more than 60 families, Hospice Austin Chaplains Katrina Shawgo and Nettie Reynolds would each routinely visit three or four homes a day to spend time with terminally ill patients and their loved ones. These visits might include bedside prayers, music, poetry readings, and deep conversations.That was before the pandemic changed everything.

“We’re all trying to maintain each other’s health and safety,” Katrina says. “A lot of the families don’t want extra people in their homes for the same reason. The last thing somebody who is already suffering with a terminal illness needs is to get the coronavirus on top of it.”

Hospice Austin is a nonprofit organization that provides end-of-life care for anyone who needs it, often in their homes, but also in hospitals and nursing homes. Eligible clients have received a diagnosis of a terminal illness with a life expectancy of less than six months, although it’s not unusual for people to live longer.

“Everybody is unique,” Nettie says. “Chaplains are here not just to show up at the very end of life. We’re here to be in that last movie of your life, to be a bit player with your family to help that movie be as joyful and calm and pain-free as possible.”

When a patient enters hospice, they are assigned a nurse, a social worker, and an interfaith chaplain. The team’s goal is to provide a support system for patients and loved ones who serve as primary caregivers. For both, an already difficult situation has been made more challenging by the pandemic.

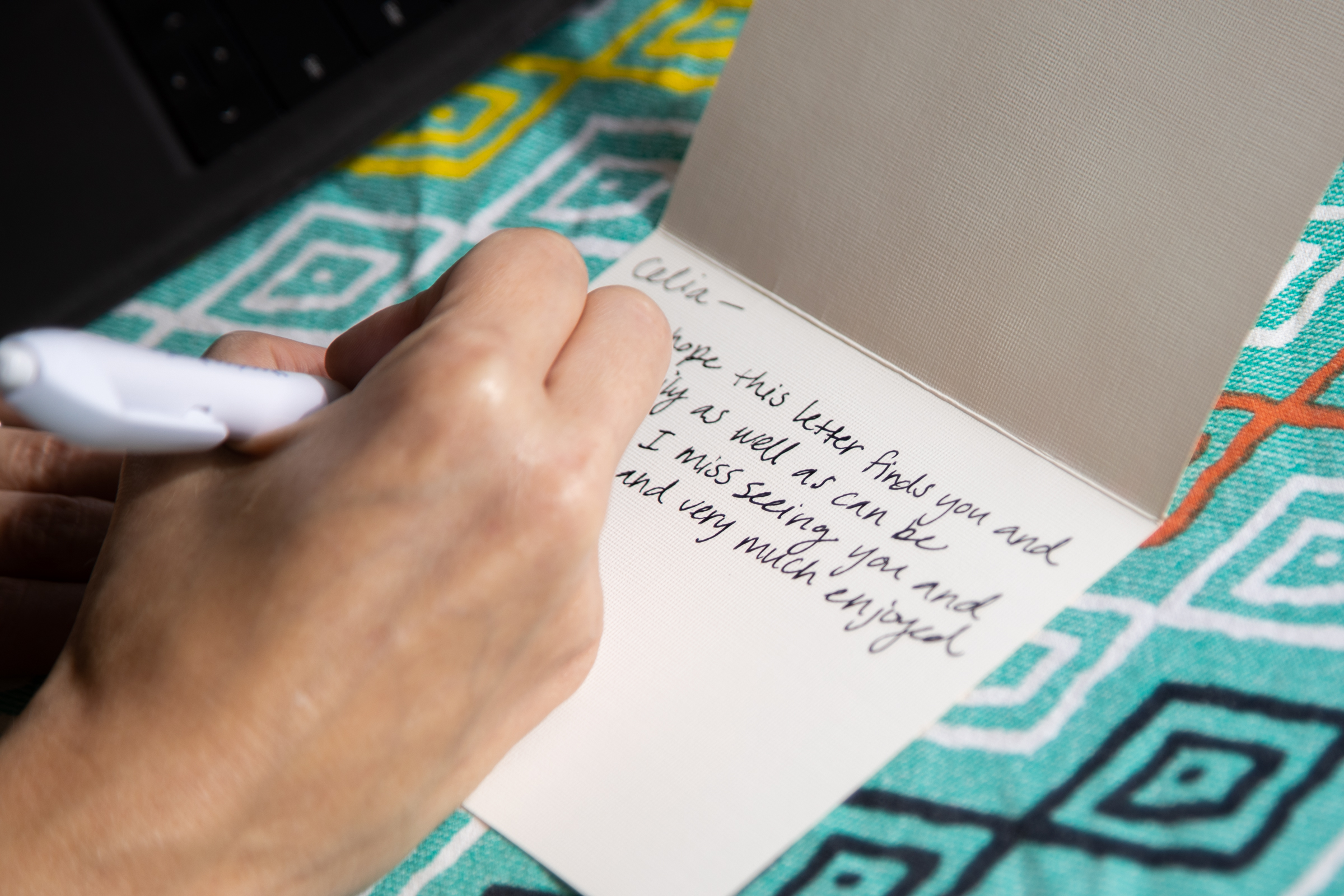

Rev. Katrina Shawgo, a chaplain with Hospice Austin, works on her back porch. Shawgo’s job has changed significantly in light of COVID-19 restrictions, and while she used to spend most of her time driving to each of her clients’ houses, she now spends most of her time on the phone. She has started writing cards to her clients because she doesn’t get to interact with them in person very often. [Photos by Kelly West]

“Caregiving is very isolating, even in the best of times,” Katrina says. ”We have people who are taking care of a loved one with dementia at home and they can’t leave them by themselves. They’ve had to work out for a long time how to get their groceries and how to get things done. So, in that sense, it’s kind of familiar, but now there’s an extra layer of isolation.”

Most in-person visits by chaplains are now reserved for “essential need” situations — when a caregiver requests a chaplain to be present for a person’s final hours, for example. Due to social distancing requirements, Nettie says, she and her colleagues are finding other ways to provide spiritual and emotional support during the weeks and months leading up to death.

“I keep telling people, ‘I know I can’t be there in person and that we’re distant physically, but we’re not distant at heart,’” Katrina says. “I keep telling them, ‘I care about you, and I care about how this goes for you and for your family.’”

Katrina says the majority of her patients are older people living in rural parts of Central Texas, with low incomes and limited access to the technology that makes video meetings possible.

“I’ve been spending a lot of my days on the phone, which is a big shift for me. My ears are getting tired of wearing earbuds,” Katrina says. “But it’s been working — so far, so good. People are really appreciative to know that they’re not out there dangling by themselves, that there’s someone who’s thinking about them and checking in.”

Since a big part of a chaplain’s role is to connect and build rapport with people, not being able to make eye contact and use body language has been an added challenge during phone calls. On the other hand, the unprecedented universal experience of living during a global pandemic at least provides something to bond over.

“That’s been my entry point for all of my patients,” Katrina says, “to talk about the struggle, both of this virus and the new way we’re all having to live, layered with having or caregiving for a terminal illness.”

Creating a connection with people while communicating remotely is also difficult without the ability to “read the room,” Nettie says. She gathers information by being in a person’s space, identifying the things they care about and also sensing whether they are comfortable or in pain, calm or agitated, based on their facial expressions and gestures. She realizes now how easy it was to take those moments of subtle connection for granted before the pandemic.

“I miss getting to say to people, ‘Tell me more,’ and holding their hand,” Nettie says. “Because it’s not the same when it’s just virtual.”

Whether over the phone or during in-person visits, Nettie uses a new practice instead of physical contact with clients and caregivers. She calls it a “heart blessing.” Before leaving an encounter with a patient and their family, she asks everyone to place their hands over their hearts “and recognize that all of humanity is united by the commonality of having a heart,” Nettie says.

“We feel our hearts beating and I say, ‘We’re beating in unison to the greater good. We are here for love, peace, and comfort, and we acknowledge each other’s hearts in this space,’” she says. “And then we just hold our hand to our heart for a minute and then I leave. Actually, it’s almost a deeper thing than just handshaking.”

Nettie says she’s likely to continue using the heart blessing even after restrictions on social interactions are relaxed. Another new technique she’ll probably keep in her repertoire is a new routine of recording herself praying or giving blessings, and then sharing those audio recordings with her patients and their families through email.

Hear one of Nettie’s blessings.

The idea came to her because her husband, a blues harmonica player, has been swapping jam band practice recordings with his musician friends. After testing out the idea and hearing positive feedback from one family, she’s made a number of recordings, including The Lord’s Prayer, Psalm 23, and her heart blessing.

Chaplain Nettie Reynolds uses video chat to meet with Hospice Austin social worker Rachel Poppers from her bedroom, which doubles as a home office. “Everybody is struggling right now,” Nettie says. “And I just so admire our social workers and our nurses and our doctor and our team leader, because I think they have much more difficult jobs than I do. I want them to feel uplifted.” [Photo by Jim Tuttle]

Providing resources and encouraging her patients’ family members to give emotional and spiritual comfort in her absence has become an important part of the chaplain role. Katrina says a young man recently called her to ask, “What should I say? Are there scriptures I could read to my grandmother that would be comforting to her?”

“While normally I would provide that in person, I give those resources to him and I say, ‘Here’s some things that you can read to her. I can email you a prayer,’” Katrina says. “So it’s been sort of a shift from, ‘OK, I’m going to relieve you of this duty by doing this in person,’ to ‘I am now going to empower you to do this part because I know it’s important to you and to your family.”

Katrina and Nettie both attended Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary, but as interfaith chaplains, they tailor their approach for each patient based on the client’s spiritual beliefs — or lack thereof.

They’ll make arrangements for Catholic patients to be anointed and for Muslim patients to consult with an imam. For non-religious individuals, Nettie says she’ll often read poetry by writers like Pablo Neruda, Mary Oliver, and Wendell Berry, to try and provide “a metaphor for what they’re going through.”

“There’s a real fear that a chaplain is going to walk in with what I call ‘a coat of many Bibles’ and hit you over the head with them, and that’s not what we do at all,” Nettie says. “We’re not there to convert people to a specific religion or spiritual path. We’re there to meet them where they are and walk alongside them and their families.”

In situations where it’s appropriate and possible for her to visit patients while maintaining a safe distance, Nettie has still been making occasional house calls. In one instance, she sat in the backyard outside a woman’s bedroom window and read Bible verses to her. In another, she wore a mask and gloves to deliver a packet of sunflower seeds to a couple who are isolated from the rest of their family.

Nettie and her patient’s husband planted the seeds in the couple’s garden while she watched from the back porch. Afterwards, Nettie talked with them about how the seeds from those flowers could be passed on to their children and grandchildren to plant for themselves. Later, the couple used video chat to show their grandchildren where the sunflowers are planted.

Chaplain Nettie Reynolds (left) hula-hoops with her next-door neighbor, which has become their weekly stress-relief routine since the pandemic started. “Everything is kind of hard right now, and we all need downtime to process what we’re feeling,” Nettie says. “It feels good just to work out that that trauma physically, sweat it out and do something joyful.” [Photo by Jim Tuttle]

“As a chaplain, it’s really important to help people understand how the continuity of the love that they give still lives on in the hearts of the little ones and big ones that they’ve loved,” Nettie says. “Even if we can’t see it, it is there. It’s present in our family pictures, or our memories, or in the growth of a sunflower that we know was planted by our grandmother and grandfather.”

Hospice Austin offers the option for a free memorial service, conducted by a chaplain, after a patient dies. Nettie has conducted four of these in the past month, adjusting her normal program to provide for adequate social distancing.

The services are held outdoors, at graveside, rather than in a church or funeral home. Attendance is limited to 10 people, including the officiant, and everyone wears masks while standing at least six feet apart. Nettie says the most recent memorial she led was to honor an elderly patient who had died of complications from COVID-19.

A long row of about 20 cars followed the hearse to the cemetery and parked, just so friends and family of the deceased could be present in some way, Nettie says. They sat in their cars with heads bowed throughout the service, and afterwards Nettie walked along the row with one hand on her heart. The experience was “humbling,” she says.

Nettie keeps all the services brief, usually about 10 minutes. In some cases, a family member records a video to share with loved ones who were unable to attend. Many plan to hold larger services at a later date, when it’s safe to do so.

In the meantime, Nettie says she has another special prayer she’s been using at the end of the day, just for herself. She calls it a “damn it prayer.”

“I think it’s okay to express all emotions, and so I always say thank you at the end of my day. I always say, ‘Please bless all my families and all my patients,’ and then I say, ‘Please, please, damn it, let this pandemic end. Amen.’ And sometimes I’ll say, ‘Please forgive me for praying damn it,’ but most of the time I don’t.”